The shift from keyword matching to contextual understanding means content creators must write for comprehension, not just discovery. AI systems don’t just match words—they understand intent, context, and the unstated needs behind every query.

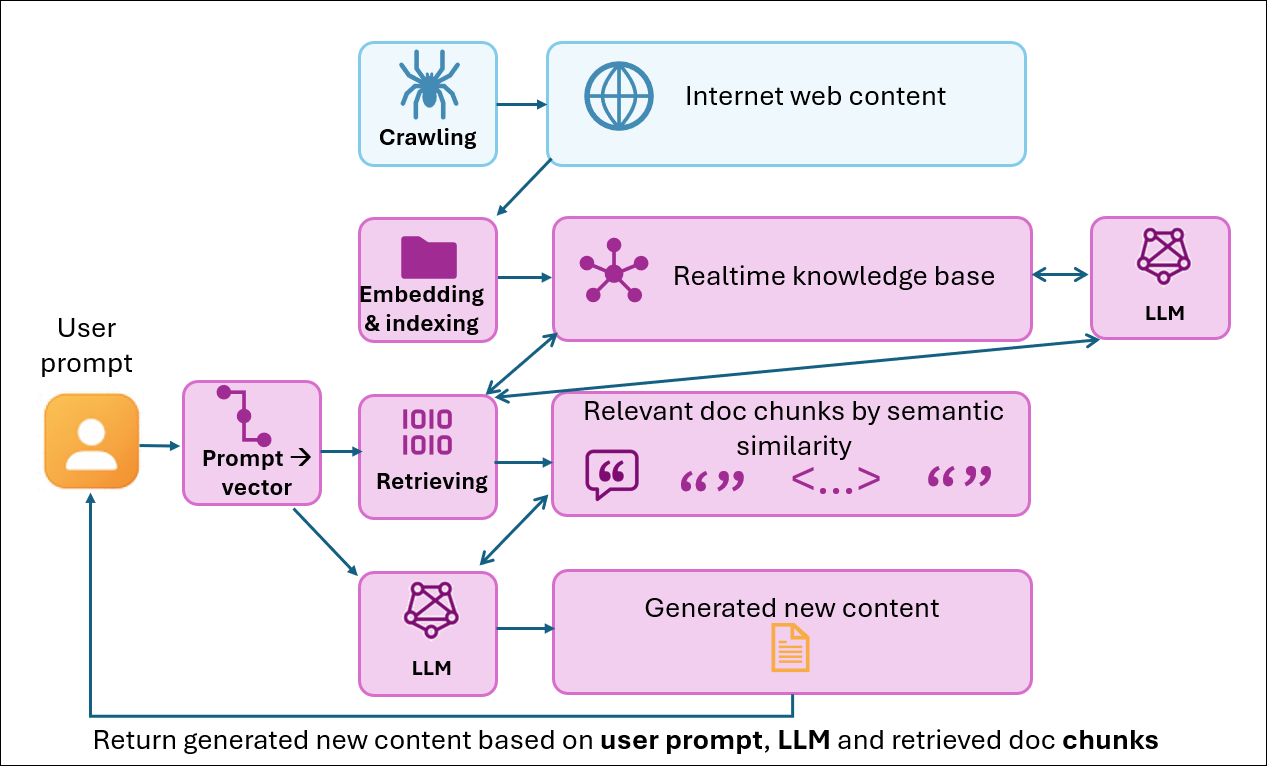

In my first post, I explored how both traditional and AI-powered search follow the same fundamental steps: crawl and index content, understand user intent, then match and retrieve content. This sequence hasn’t changed. What has changed is now AI-powered search embeds Large Language Models (LLMs) into each step.

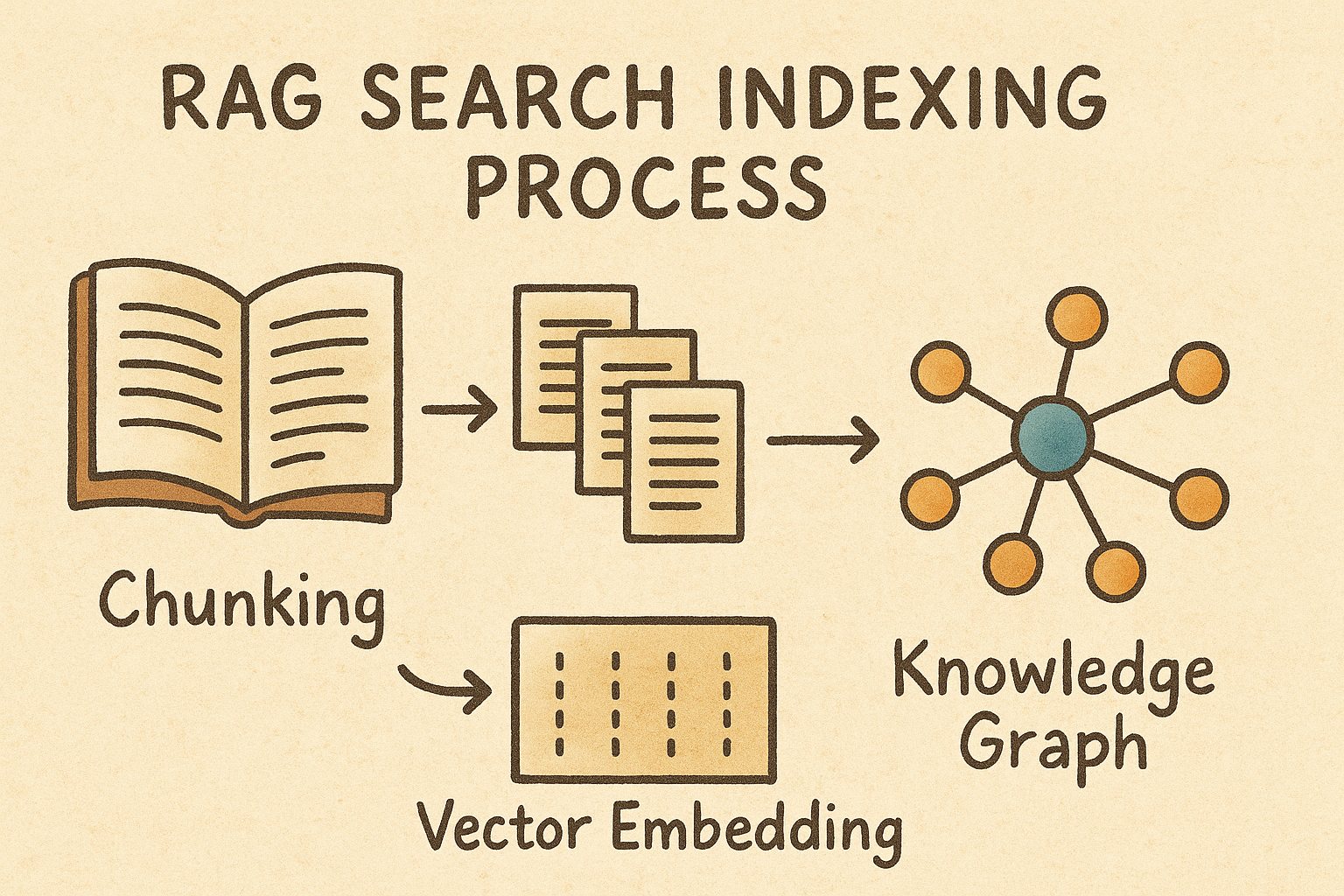

My last post dove deep into indexing step, explaining how AI systems use vector embeddings and knowledge graphs to chunk content semantically. AI systems understand meaning and relationships rather than cataloging keywords.

So what’s different about user query (intent) understanding? When someone searches for “How to make my computer faster?“, what are they really asking for?

Traditional search engines and AI-powered search systems interpret this question in fundamentally different ways. , with profound implications for how we should create content.

The Evolution of Intent Understanding

To appreciate how revolutionary AI-driven intent understanding is, we need to look at how search has evolved.

Early traditional search engines treated question words like “how,” “why,” and “where” as “stop words”—filtering them out before processing queries.

Modern traditional search has evolved to preserve question words and use them for basic query classification. But the understanding remains relatively shallow—more like categorization than true comprehension.

AI-powered RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) systems represent a fundamental leap. They decode the full semantic meaning, understand user context, and map queries to solution pathways.

Modern Traditional Search: Pattern Recognition

Let’s examine how modern traditional search processes our example query “How to make my computer faster?”

Traditional search recognizes that “How to” signals an instructional query and knows that “computer faster” relates to performance. Yet it treats these as isolated signals rather than understanding the complete situation.

Traditional search processes the query through tokenization, preserving “How to” as a query classifier while removing low-value words like “my.” It then applies pattern recognition to classify the query type as instructional and identifies keywords related to computer performance optimization.

What it can’t understand:

"My” implies the user has an actual problem right now—not theoretical interest- “

Make...faster” suggests current dissatisfaction requiring immediate solutions - The question format expects comprehensive guidance, not scattered tips

- A performance problem likely has multiple causes needing different approaches

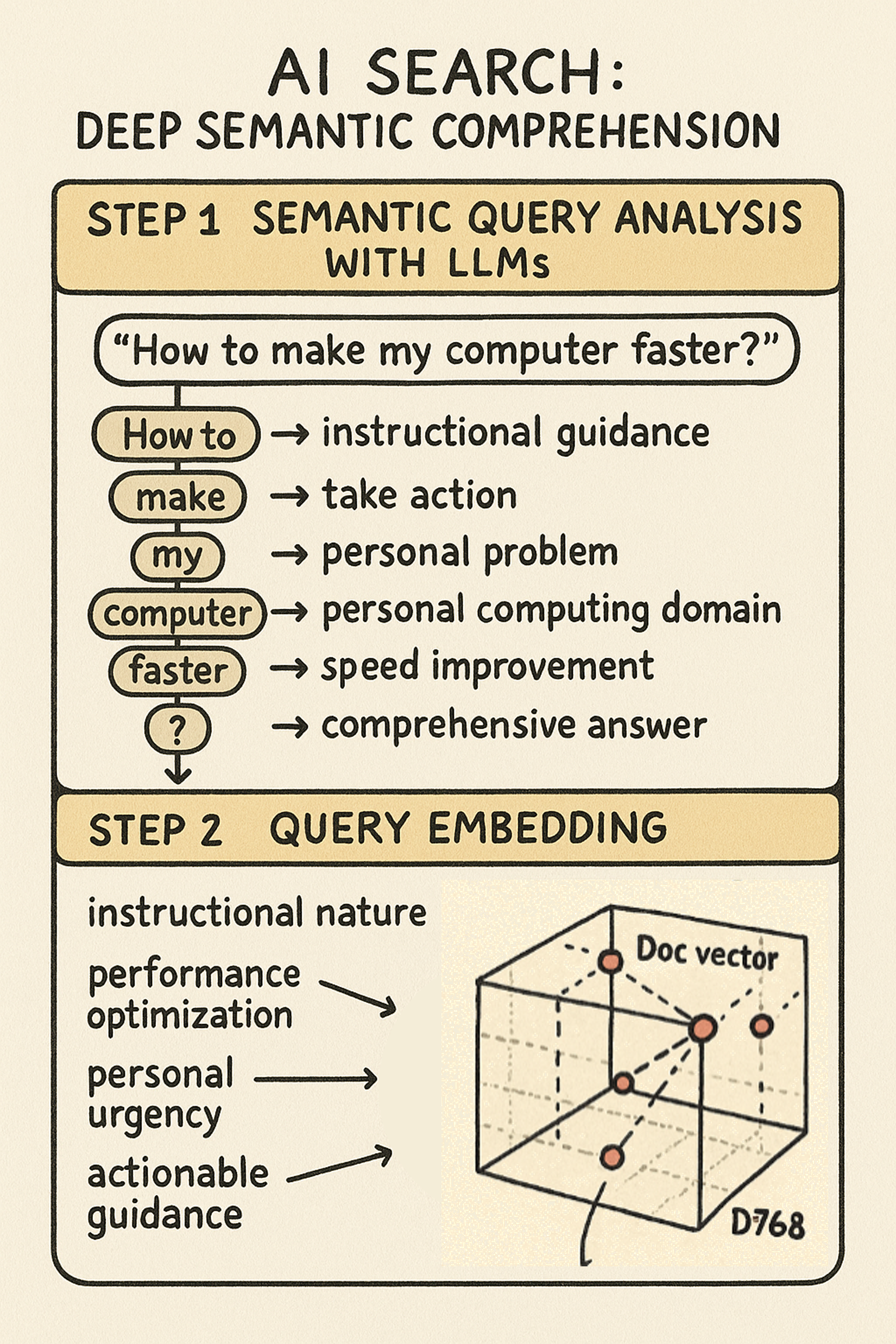

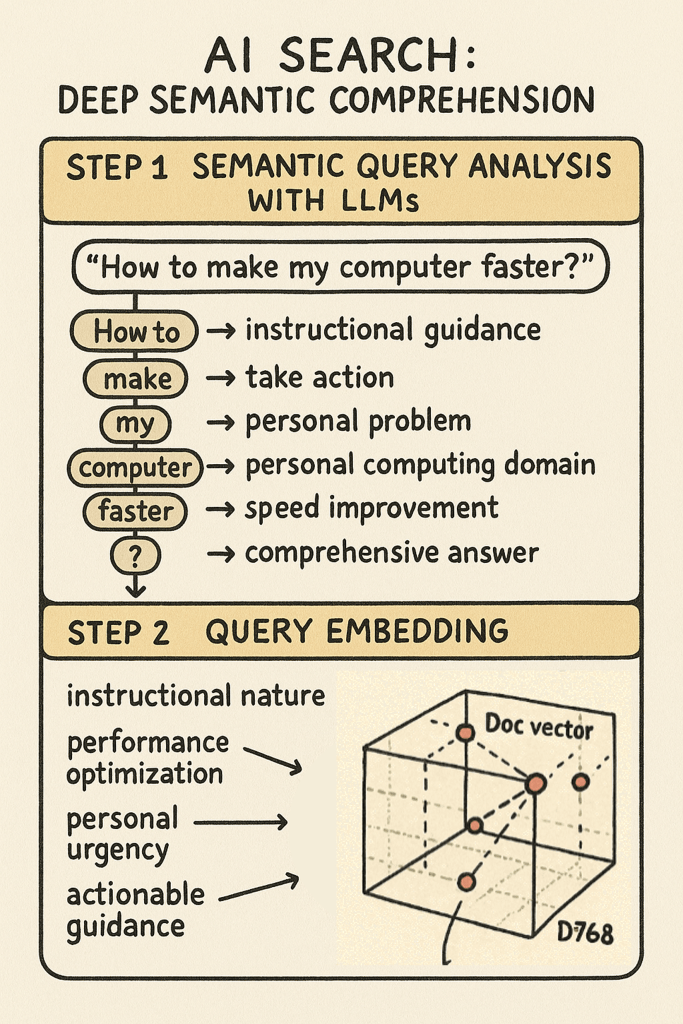

AI Search: Deep Semantic Comprehension

RAG systems process the same query through multiple layers of understanding:

Semantic Query Analysis When the AI receives “How to make my computer faster?”, it decodes the question’s semantic meaning:

- “

How to“ → User needs instructional guidance, not just information - “

make“ → User wants to take action, transform current state - “

my“ → Personal problem happening now, not hypothetical - “

computer“ → Specific domain: personal computing, not servers or networks - “

faster“ → Performance dissatisfaction, seeking speed improvement - “

?“ → Expects comprehensive answer, not yes/no response

The LLM understands this isn’t someone researching computer performance theory—it’s someone frustrated with their slow computer who needs actionable solutions now.

Query Embedding The query gets converted into a vector that captures semantic meaning across hundreds of dimensions. While individual dimensions are abstract mathematical representations, the vector as a whole captures:

- The instructional nature of the request

- The performance optimization context

- The personal urgency

- The expected response type (actionable guidance)

By converting queries into the same vector space used for content indexing, AI creates the foundation for semantic matching that goes beyond keywords.

The Key Difference While traditional search sees keywords and patterns, AI comprehends the actual situation: a frustrated user with a slow computer who needs comprehensive, actionable guidance. This semantic understanding of intent becomes the foundation for retrieval and matching.

How Different Queries are Understood

This deeper understanding transforms how different queries are processed:

“Where can I find Azure pricing?“

- Traditional: Matches “

Azure” + “pricing” + “find“ - RAG: Understands commercial evaluation intent, knows you’re likely comparing options

“Why is my app slow?“

- Traditional: Diagnostic query about “

app” + “slow“ - RAG: Recognizes frustration, expects root-cause analysis and immediate fixes

What this Means for Content Creators

AI’s ability to understand user intent through semantic analysis and vector embeddings changes how we need to create content. Since AI understands the context behind queries (recognizing “my computer” signals a current problem needing immediate help), our content must address these deeper needs:

1. Write Like You’re Having a Conversation

Remember how AI decoded each word of “How to make my computer faster?” for semantic meaning? AI models excel at understanding natural language patterns because they’re trained on conversational data. Question-based headings (“How do I migrate my database?“) align perfectly with how users actually phrase their queries.

Instead of: “Implement authentication protocols using OAuth 2.0 framework” Write: “Here's how to set up secure login for your app using OAuth 2.0“

The conversational version provides contextual clues that help AI understand user intent:

“Here's how” signals instructional content, “your app” indicates practical guidance, and “secure login” translates technical concepts to user benefits.

2. Provide Full Context in Self-Contained Sections

AI understands that “How to make my computer faster?” requires multiple solution types—hardware, software, and maintenance. Since AI grasps these comprehensive needs through vector embeddings, your content should provide complete context within each section.

Include the why behind recommendations, when different solutions apply, and what trade-offs exist—all within the same content chunk. This aligns with how AI chunks content semantically and understands queries holistically.

3. Use Intent-Driven Metadata

Since AI converts queries into semantic vectors that capture intent (instructional need, urgency, complexity level), providing explicit intent metadata helps AI better understand your content’s purpose:

- User intent: “

As a developer, I want to implement secure authentication so that user data remains protected“ - Level:

Beginner/Intermediate/Advancedto match user expertise - Audience:

Developer/Admin/End-userfor role-based content alignment

This metadata becomes part of the semantic understanding, helping AI match content to the right user intent.

The Bigger Picture

AI’s semantic understanding of user intent changes content strategy fundamentals. Content creators must now focus on addressing the full context of user queries and consider the implicit needs that AI can detect.

This builds on the semantic chunking we explored in my last post. AI systems use the same vector embedding approach for both indexing content and understanding queries. When both exist in the same semantic space, AI can connect content to user needs even when keywords don’t match.

The practical impact:

AI can now offer comprehensive, contextual answers by understanding what users need, not what they typed. But this only works when we create structured content in natural language, complete context, and clear intent signals.

This is the second post in my three-part series on AI-ready content creation. In my first post, we explored how AI indexes content through semantic chunking rather than keyword extraction.

Coming next: “Beyond Rankings: How AI Retrieval Transforms Content Discovery”

Now that we understand how AI indexes content (Post 1) and interprets user intent (this post). My next post will reveal how AI systems match and retrieve content. I’ll explore:

- How vector similarity replaces PageRank-style algorithms

- Why knowledge graphs matter more than link structures

- And what this means for making your content discoverable in AI-powered search